OK: the first of these marriages -- of the Los Angeles-based food critic Jonathan Gold to his wife Laurie Ochoa, his former editor -- seems to work wonderfully well both personally and professionally. But it's the second one -- Mr. Gold as a superlative food critic to his hometown and still favorite city, Los Angeles -- that is the proverbial marriage-made-in-heaven. Thanks to the work of filmmaker Laura Gabbert, shown below, we learn a lot about both of these couplings, while enjoying the experience immensely.

Ms Gabbert has the good sense to keep her documentary, CITY OF GOLD, focused heavily on her subject, and Mr Gold (shown above and below, in two of his haunts) proves an intelligent, thoughtful, warm and gracious host -- in the process almost convincing TrustMovies, a former born-and-raised Angeleno who used to hate this would-be city, that it might be pretty damned wonderful, after all. It certainly offers the most amazing array of tasty and varied restaurants that anyone could ask for -- even if you have to drive for hours to get to many of them. Lengthy drives, usually in heavy traffic, have become -- ever since the destruction of the city's fabulous public transportation system during the late 1940s and early 50s -- indigenous to Los Angeles.

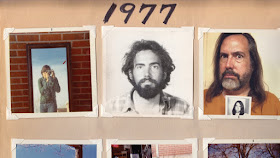

Ms Gabbert gives us only snippets of Gold's writing, but these are enough to make us want to go to the source and read more. She weaves history, tradition, diversity and all kinds of food and restaurants -- all of which are filtered through Mr Gold's lovely sensibility -- into the tale of a "critic" who ups the standard for criticism via... well, you'll see. And hear. His thoughts about just about everything seem well worth knowing. He calls one little place a "miracle of entry-level Capitalism" and he and his director have a good time making fun of the "anonymous restaurant critic" (below) -- an idea which he thoroughly pooh-poohs.

We come to understand how and why this critic chooses the restaurants he does -- often family run and what some of us might call a tad "low-end." The reason is because the owners and chefs are cooking for their community, rather than for critics or tourists or "haute cuisine-ists." It turns out that Gold never reviews a restaurant until he has frequented it several times (I believes he mentions that his record is 17 times prior to review). Clearly this is no rush-to-judgment kind of guy. He also, toward the end of this really excellent documentary, explains something that is epidemic to criticism and that he attempts to derail: the idea of "contempt prior to investigation." Gold appears to lack the former but works hard to accomplish the latter.

That last explains a lot about this man and his mission, I think. (He's as likely to cover someone's "taco trailer," above, as go to a sit-down restaurant.) So sit back and enjoy the many interviews with restaurants owners, chefs, and other critics (Ruth Reichl makes an appearance here, too), along with Gold's family and friends. Together all this becomes a genuinely new and revealing look at a place we often take for granted, its enormously diverse people, and the food they cook, eat and share.

City of Gold, from Sundance Selects/IFC Films and running 96 minutes, after opening in New York and Los Angeles hits South Florida tomorrow in the Miami area at the O Cinema- Wynwood.