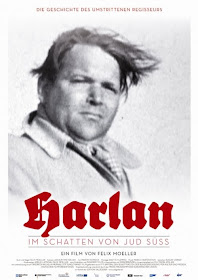

Viet Harlan (1899-1964) was a German filmmaker/

actor most promi-

nent during the the time of the Third Reich. I wager that a good portion of film buffs, TrustMovies included, will not have heard of Herr Harlan prior to viewing the docu-

mentary by Felix Moeller (shown below) entitled HARLAN: In the shadow of Jew Süss. First seen at a documentary festival in Germany in the fall of 2008, the film was then given a German theatrical release a year ago.

So far as I can detemine it has not been released anywhere else -- until now, thanks to Zeitgeist Films, which is opening it this Wednesday at New York City's Film Forum for a two-week run. The weird thing is, now that I have seen this documentary, I rather wonder why. I do not mean that this film about Harlan, his "work" and his family is uninteresting (it's hard to recall anything Holocaust-related that does not possess a modicum of fascination). And the fact that Harlan's oeuvre, as we learn here, included perhaps the most infamous of the anti-semetic diatribes of German Nazi-era cinema -- the 1940 narrative film Jew Süss -- would seem to make this guy a shoo-in for the spotlight.

Yet Moeller's movie is less about Harlan than about his remaining family (photos of whom are shown above and below, throughout this post). The filmmaker has obviously spent a lot of time tracking these people down and engaging them in conversations about their progenitor's film -- how they feel about it, and him. From these conversations, and there are many, we see just about every response imaginable to the "burden" this family now bears: guilt, anger, resignation, excuses, leave-us-the-fuck-alone, near-silence, befuddlement, sorrow, let's-get-on-with-our-lives and maybe a dozen more "variations on a theme."

All of this is utterly to be expected and there is barely a surprise in the bunch. Intelligent viewers, aware of history and the human condition, could probably write most of these conversations themselves and perhaps make them a lot juicier, pointed, caustic and moving. Of course, this is why we have narrative films. Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss runs only about 100 minutes, but it seems much longer. By the end, I was more than ready to remove myself from this family who accomplishes little else than proving itself unworthy of a documentary -- just as Viet Harlan, on the basis on what Moeller shows us here, appears a second-rate filmmaker who, though he may have aspired to it, was unlikely to touch the hem of Douglas Sirk's garment.

It is not that these family members are stupid or unintelligent; it's simply that, even as they take opposing viewpoints, they give us again and again little more than the expected. I suppose you can view them as a microcosm of German society and its "take" on the Holocaust and German guilt. But if you've been following this story as long as I have, a shrug is likely to be your response, followed by, "Yes. And...?" Harlan's first wife, it turns out (or maybe his second, I wasn't entirely clear on this point) was Jewish, so out of "necessity" he divorced her. His granddaughter from this marriage Jessica Jacoby, shown below, is the only character we meet who seems to represent the "other." And, no surprise, she's angry.

Toward the middle of the movie there is a scene, just post-WWII, in which Harlan and his wife are thrown out of a theater when the audience realizes who they are. The fine irony here, which goes unmentioned, is that the same people who were now jeering Viet were but a few years before cheering him for the very thing they now condemn. What does this say about the German citizenry-at-large? Pretty much the same thing you could say about the citizenry of any country -- who would likely behave the same way -- pre-, during, and post-Holocaust. Yes, it's the same' ol same ol': hypocrisy, denial and a very short memory.

I wonder what Herr Moeller, the son of renowned German director Margarethe von Trotta (whose films include Marianne and Juliane and Rosa Luxemburg), expected to learn from this family -- most of whom, with a couple of exceptions, draw into themselves and shut their communicative doors, as families under perceived threat are wont to do. They would prefer that all this would simply go away. For the most part, it has. But something always remains. A few more generations down the road it will all -- or most -- be forgotten, which is, of course, a blessing. And a curse.

What the film finally accomplished, for me, is to engender a bit of a desire to view in its entirety the actual Jew Süss (the poster art for which is shown below) to find out exactly what kind of experience Harlan (shown above, in his heyday) offered to his more-than-willing-to-watch German public.

You can view the Film Forum playdates and screening times for Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss here.

No comments:

Post a Comment