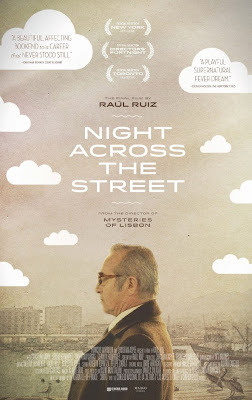

To answer the question in the headline, if this is not the loveliest, most playful, profound and artful of good-byes, then it is certainly up there will the best of them. Having just removed the screener from my Blu-ray player and still a bit high from this filmmaker's quiet visual pyrotechnics and verbal poetry, coupled to the idea that we will have no more from the man -- born Raúl Ernesto Ruiz Pino and later known as the filmmaker Raoul Ruiz and even later as Raúl Ruiz -- who died a year and one-half ago, I probably should wait a bit before trying to write about this particular confluence of art and leave-taking, for fear that sentimentality will prove too strong a force. But as the film opens today, and I have promised to cover it, let's just... wing it.

NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET (an intriguing title that I cannot begin to explain: how is this different from night next door?) offers many of the same themes and styles that always seem to have attracted Señor Ruiz, among them exile and identity, present and past, young and old, life and death, the corporeal and the ghostly, the experimental and the surreal, and theory brought to odd life -- regarding film and just about everything else. Born and raised in Chile, Ruiz worked as a filmmaker until the U.S.-aided Pinochet coup, when he escaped to France, where he lived and continued to work over the decades. As I understand it, toward the end of his life, he returned to Chile to make this final film (plus a few others as yet unseen by us hoi polloi). I've only viewed maybe a dozen of his enormous output of 117 (both shorts and full-lengths), but it does seem to me that this "Night" is not only his best but in many ways the apotheosis of his oeuvre.

For one thing it is infinitely playful. Did this filmmaker's touch continue to lighten even as he grew older? It would seem so, as both this film and his penultimate work, Mysteries of Lisbon, are among his most playful without being quite so insistently confusing as some of his earlier films. (Or maybe I've just grown up enough to better appreciate him.)

Ruiz's last film begins with some aerial shots across landscapes and then seascapes. Then we're in a classroom (above) in which a professor attempts to teach his class of students -- young, older and very old -- how to see and hear with their eyes shut. Instead of beginning with something remotely normal and then morphing into the surreal and bizarre, we seem to be there already -- but in a more playful fashion than usual.

We meet our hero, Celso as both a boy and old man, and in bits and pieces come to learn something about his/their life and interests. We meet Beethoven, the real deal (see photo at bottom), or at least as Ruiz conceives him, and we even make a trip to the cinema with him (the composer is amazed, as indeed he should be). Time jumps all over the place, and so does the "reality" of some of the sets. Clearly, we're seeing our characters at times against obviously superimposed backdrops, and with some things simply drawn in (note the curtain on the window, above).

All this is just "there," for us to note or not. There is a wonderfully confused political discussion at a soccer game (above) which to my mind reflects the politics of Chile, even today. And we're soon made aware of an assassination plot against our poor Celso, who is about to retire from his office job, where his seemingly oncoming dementia is worsening. Or maybe he's simply preoccupied. (When we find out just who the assassin is, it's mind-bending.)

There's a large cast here, and most of them manage to remain light and nimble against what I can only describe as great odds of having to (and perhaps not able to) know what the hell is really going on. But they're game, and somehow, even if they don't quite understand, I think we finally can and do. This is Celso's life, in its specifics -- adventure in its literary form, with pirates (below, in background) and poetry jousting for pride of place -- but it is also, somehow, all of our lives. In contemplating his own mortality, Ruiz is showing us ours.

Just what are the facts of Don Celso's life? There don't seem to be many than are definitive or that we can hang on to. Yet history -- or maybe it's simply imagination -- appears to be repeating itself, but in a different mode. In the Ruiz world, a super-violent crime comes across as something almost wistful, a hint of the past wafting through the window like an aromatic little breeze. Well, anyway, no such thing happened, our hero assures us.

By the by, it is suggested that we're afraid of both staying and of leaving. Well, when leaving means something rather permanent, as here, of course we are. But that's humanity for you. Toward the end we learn how a camera is like the inside of a gun barrel (above) -- and this is one of the most wonderful visual effects I've yet seen. As is the symbolic meeting of the young and old Celso, below, which is simple and so very effective.

The movie can only make you think: My god, what a life this fellow Ruiz really had -- if only in his imagination. Night Across the Street never loses its unique playfulness, no matter how weighty the themes that are tackled. I don't see how the filmmaker could have gifted us with a more teasingly profound yet graceful good-bye.

Ruiz's movie, via The Cinema Guild, opens today, Friday, February 8, in New York City at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center. I don't see any other upcoming playdates, but surely some new ones will appear soon.

Photos are from the film itself, except for that of Señor Ruiz,

which comes courtesy of Getty Images.

No comments:

Post a Comment