the Civil War, and their encounter with a wounded Yankee soldier who winds up in their charge.

The early film, a poster for which is shown above, was a vehicle for a quite handsome Clint Eastwood, with Geraldine Page and Elizabeth Hartman (both now deceased) as the female protagonists.

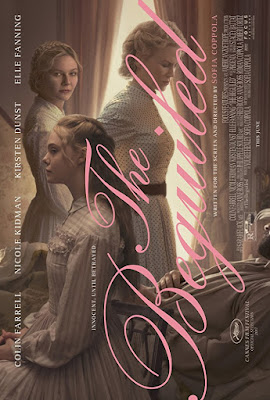

In the 2017 version (at left), Director Sofia Coppola’s cast headlined Colin Farrell, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, and Elle Fanning.

The near-identical plots are hot-house steamy, although one generates much more steam than the other: 12-year-old Amy (Pamelyn Ferdin, above, 1971) is picking mushrooms in the woods when she comes across wounded Yankee Colonel John McBurney and helps him back to the columned plantation manse, (Miss Martha Farnsworth’s Seminary for Young Ladies), where the students, their teacher, Miss Edwina, and Headmistress Martha nurse the soldier. Fear of the enemy is displaced by sexual yearnings that simmer to a boil — and big trouble. McBurney proposes to Miss Edwina, but the school hussy has lured him into bed where Edwina discovers them. In her rage a scuffle ensues and McBurney tumbles down stairs, shattering his leg. Miss Martha cuts it off, (her own erotic stirrings for their guest had felt betrayed). Much more rage ensues, and Amy is dispatched to the forest to find the not-good kind of mushrooms for their now unwelcome visitor. He will be longed for but not mourned. The shock to their system removed, peace and harmony is restored to the sisterhood in the small seminary at the large plantation house. Below is the 2017 cast, including Miss Edwina, (Ms Dunst, at left) and Miss Martha (Ms Kidman at right); center is Ms Fanning, who plays the hussy.

Despite its being the same tale, the two films feel quite different and are worth viewing to see what the two directors do with the same material. The 1971 version was like a steam kettle fired up by the commotion of the sex, drugs, rock-roll 1960-70’s; anti-Vietnam war sentiment; and women’s lib and civil rights protests. The slave South and the Civil War made vivid backdrops for rising civil rights and anti-Vietnam consciousness, but the fear by men of emasculating women plus female rage at male patriarchy were the film’s driving emotions during the heyday of Betty Friedan and bra-burning. The riled-up anxieties of the era — Freudian fear coupled with budding political enlightenment — ruled the brains of the male movers of the ’71 “Beguiled’.

With Eastwood as the Yankee and directed by his oft-time collaborator, Don Siegel (Dirty Harry, Escape from Alcatraz), the atmosphere reflects Siegel’s blatant tell that ‘Beguiled’ is about “the basic desire of women to castrate men”. Eastwood’s McBurney, however, was no innocent; he deserved what he got. Siegel uses McBurney’s caddishness to show that the Corporal’s brand of patriarchy deserved its comeuppance. From the first encounter with little Amy, pronouncing her ‘old enough for it’ with a long adult kiss, to his relentless romancing and manipulation of the other women, McBurney was one leonine fox to avoid in the woods or henhouse.

The slave Hallie (Mae Mercer) who labors for the school speaks to early civil rights political correctness. She is the only woman who is not at all deceived by his blandishments. When McBurney threatens rape she taunts back: “You’d better like it with a dead black woman because that’s the only way you’d get it from this one”. One critic said that there is not enough cinema that is as unabashedly horny as this old film. It is not just horny, but full of female hysteria, fear, and fantasy. (Miss Martha is revealed to have had an incestuous relationship with her dear departed brother; she dreams of three-way sex with him and Miss Edwina.) All the skeevy heat makes for an entirely campy romp seasoned with a dash of True Blood, only slightly diminished by the dated filmmaking tropes of the seventies.

At the time it was a box office flop; the Trumpian Eastwood suggested that his fans didn’t support his he-man persona being cast as the women’s victim. But the film has since found its audience, scoring 92+% approval on Rotten Tomatoes and considered one of Eastwood’s finest, especially by the French. Meanwhile at Cannes the ‘Beguiled’ remake won Sofia Coppola a best director prize exactly a year ago, only the second time a woman has won for direction at the festival. The accolade may have been a hasty swoon over the Coppola image and Spanish hanging moss (see the very last image). I doubt her version will become a classic like Siegel and Eastwood’s, despite the loveliness of the imagery by Philippe Le Sourd, a stunning sound score, and a cast led by A-listers. Scenes shot through giant arching trees dripping with moss and ladies framed in lace are very beguiling (that's Dunst as Miss Edwina below). Coppola has been reported saying that she wanted to tell the story from the point of view of the “female gaze”, which is to say, the opposite of the male castration fear fantasy. She succeeded in trodding gently on Freud compared to the old film, but the implementation of her own strategy was not a winning formula.

In Coppola’s version the handsome injured soldier is not devious scum but a handsome average bloke (Mr. Farrell, below) destined by accident to outlive his battle wounds only a bit longer than he otherwise might have expected.

Coppola’s gracious Southern mansion is stripped bare of politics, race, and war (despite a boom here and there of distant cannons). It’s essence is the intimate world of the young and middle-age women — interdependent flowers of the South, noble in the heroism of their lost cause, mythically ‘gone with the wind’. Here is no Freudian fantasy but a portrait of women as social beings in survival mode rather than passive sex objects. Their men are dead or fighting and they are isolated in a world of frustrated desires. Coppola switches up the perspectives of the women not to diminish men but rather to acknowledge each other as women.

Coppola is at home in the rarified setting; here it takes the form of a gauzy feminine world of pinks, creams, and lavender, patterned social rituals, and decorous manners— whether being held tight to the graces of the antebellum South or as in an earlier Coppola movie, at the palace of Marie Antoinette. According to NYTimes reviewer, A.O. Scott, her worlds are “designed to quarantine [their] privileged residents from the disorder and misery of life.” A particular objection to her version is said to be the whitewashing of slavery by leaving it out (Hallie is much missed). Coppola’s reason, she said, was that to have touched on the subject without doing it justice was simply not the story she wanted to explore.

This filmmaker is surely mistress of her own subject matter, but her choice to use the pulpy plot of the original “Beguiled” did her no favor given its current reputation as a classic. Her refined ‘female gaze’ embedded in the raunchy plot points does not compete with the salacious hotbed that Eastwood and Siegel exploited with such relish (above).

A female-centric story of women isolated during the Civil War perhaps should not be hung on a tale of such lurid facts as “The Beguiled”. (The James Ivory film of Henry James’ The Golden Bowl in 2000 comes to mind as powerful treatment of a story in which quiet violence is embedded into domestic ritual and manners.) Coppola’s ‘Beguiled’ lacks suspense or sexual tension. The extreme events that happen here drown out the feminine affect that Coppola sought. She fell into the trap of failing to compete with the entertainment value of the original or of enabling the female gaze to mount in intensity. I nevertheless liked the exercise of watching both versions to see the differences in mind-set and production values — and it is a provocative story.

The above post is written

by our monthly correspondent,

Lee Liberman.

No comments:

Post a Comment