As co-written (with Catenia Lermer) and directed by Simon Stadler (the latter shown at right) -- this is a first film for each of them -- the movie makes up in simplicity, honesty and feeling what it may lack in slick professionalism. It captures the character -- individually and as a group -- of this unusual Ju'Hoansi tribe in ways that range from funny and charming to quietly compelling. The movie also makes its points without condescension -- to both those natives and the western world with which they must increasingly interact.

Initially, it's the western world that comes to them. "The first time we saw the white man, we thought it was a ghost," one of them explains (hence the movie's title), and even when the tribe gets to know the western world and its discontents, it still remains unconvinced. "Sometimes white people are crazy," one explains. "They want too much and work too much, and it seems they never sleep.” Amen.

Seeing a homeless man begging in a German city, "It seems white people can also be poor." Still, the tribe is indeed learning the ropes of "civilization." As one of them notes, "We have to work with the tourists to survive." First the whites and their crew get to know the natives (and so, of course, do we) and then they take them on a kind of "field trip" to the modern world. Seeing the tribe and its first experiece in a supermarket is as much of a wonder to us as the supermarket is to them.

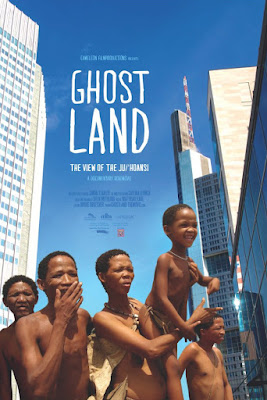

Perhaps the most interesting part of the film takes our tribe into the world of another African tribe, the Himbas (that's a Himba woman, above), and the interplay is fascinating. Then the opportunity arises for four of the natives to take an extended trip to Germany where they will mix and even "teach." From being up in that airplane they watched at the film's beginning to taking a trip in the subway ("We are under the earth!"), the four tribe members take in our modern world in wonder but with irony and intelligence. And yes, they do teach.

The update we learn in the end credits is both helpful and sad. One wishes to know why certain events occurred. In fact, there is a lot more we might have learned here. But the filmmakers obviously preferred to simply watch and listen, rather than do a lot of questioning. Even so, what we see, hear and feel should make budding anthropologists thrill, and folk who love documentaries just happy to have experienced the film.

From Cargo Film & Releasing and Autlook Film Sales, Ghostland opens tomorrow, Wednesday, December 14, in New York City for a two-week run at Film Forum, Elsewhere? Not sure. But you can at least learn more via the film's website.