E.M. Forster (1879-1970) stopped publishing fiction at age 45 although he lived on until 91, as essayist, lecturer, librettist, and broadcaster with a post at Cambridge — esteemed in the intellectual life of Europe. Why he stopped delivering the novels that so distinguished his youth was puzzled over. An untraditional biographer, Wendy Moffat, professor of English at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, retold his story (E.M. Forster:A New Life, 2010) through the viewfinder of his homosexuality. Although other biographers had revealed his orientation years before, Moffat’s unusually provocative version (her critics object to her giving short shrift to his major novels) resulted from her having turned up a diary and other materials that had not figured in earlier discussion about Forster’s life and work. She found dozens of short stories unpublished until recently, although his one homosexual-themed novel, Maurice, debuted a year after his death in 1971.

Forster’s late-life fiction is thought not to measure up to his early novels. The early work sprang from deeply-held liberal social and political views. Forster’s great-grandfather, Henry Thornton, was an abolitionist leader who supported William Wilberforce’s activism in Parliament that ended the slave trade. Forster wrote an under-appreciated biography (1956) of his great-aunt: Marianne Thornton 1797-1887; A Domestic Biography that told the story of the anti-slavery Clapham Sect liberals, especially Marianne’s brother, Henry Thornton, as well as Forster’s own family history. (My review of Amazing Grace, the story of Wilberforce and Thornton, is here.)

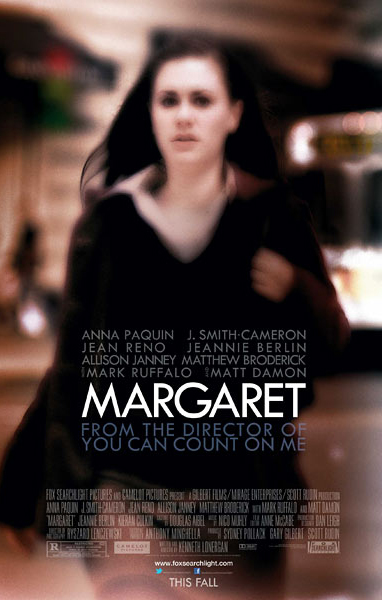

Howards End, the novel (1910), expressed both Forster’s (the writer is shown at left) socio-political views and his belief in the need ‘to connect’, a head-vs-heart story reveling in industry and technology’s effect on everyday Edwardian life. The acclaimed Merchant-Ivory and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala film of 1992 on Netflix is now joined by the 2017 BBC mini-series adapted by Kenneth Lonergan (Manchester by the Sea, Margaret) and directed by Hettie Macdonald on Starz for your comparison. Three families represent three social classes whose views represent the tensions in the story. The Wilcoxes are nouveau richer-than-rich, their fortune made in the (exploitative) rubber industry in the colonies; the young Schlegel siblings are comfortable enough to live off their inheritances (most like Forster’s own history). The Basts are poor, their windows rattle from trains thundering by. Leonard Bast, who seeks self-improvement, meets Helen Schlegel at a comically pretentious Ethical Society ‘Music and Meaning’ lecture-demonstration of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony (1992). The Schlegel’s do-gooding brings about tragedy for him in the end—Forster’s lessons being that good intentions only go so far, liberalism itself has its own pretensions, and plutocrats can be mindlessly cruel.

Henry Wilcox is a master of efficiency and ignores the poor except as a source of exploitation. His wife Ruth (above, Vanessa Redgrave, the Wilcox matriarch,1992), lacking interest in women’s rights and the arts, is nevertheless deeply attached to nature through her inherited ancestral home, Howards End, (just one of several glorious dwellings in the real estate aspect of this story). The Wilcoxes and the Schlegels have met in Europe and taken a fancy to each other. The upper-class bohemian sisters Margaret and Helen and their brother Tibby (below, Margaret and Helen, 1992) are literate, intellectual, and consumed with the arts and the causes of the day such as suffrage and the plight of the poor. They remind us (blue staters) of our liberal guilt. They prize connection, truthfulness, kindness. The Wilcoxes on the other hand, practice self-repression and lack intuition or empathy — their wealth is their pleasure; they talk only of business and sports. Son Charles Wilcox, James Wilby (1992), says: …"those Schlegels...putting on airs with their ghastly artistic beastliness." These two families intrigue each other at first—they are titilated and unnerved by their differences. Helen tells Meg of her visit to the Wilcoxes at Howards End (2017): "When I said I believed in the equality of the sexes, he [Mr. Wilcox] gave me such a sitting down as I have never had! And like all really strong people he did it without hurting me... he says the most horrid things about women’s suffrage -- nicely."

Forster has set up the social mismatch in the name of rising above differences ‘to connect’; a comic-tragic drawing-room imbroglio follows involving the disposition of Howards End (below, 1992). For after all, the one thing they do have in common is their preoccupation with real estate — they either dream of it, seek to acquire it, or have just moved in or out of it.

Ruth Wilcox and Margaret bond over the pastoral beauty and earthiness of Howards End. Their mutual fondness leads Ruth to handwrite a note on her deathbed requesting that Howards End be given to Margaret, knowing its rustic simplicity would be truly cherished. Widower Henry brushes off his wife’s dying wish, and despite none of the Wilcoxes’ having affection for the sprawling country house (son Charles calls it ‘a measly little place that never really suited us’), Ruth’s handwritten note is tossed in the fire. However, the newly bereaved Henry Wilcox courts Margaret.

Margaret says to querulous Helen about her engagement to Henry (2017): "I don’t intend him…to be all my life…more and more do I refuse to draw my income and sneer at those who guarantee it….I don’t intend to correct him or to reform him, only connect. I’ve not undertaken to fashion a husband to suit myself using Henry’s soul as raw material." Margaret sees the good in Henry and admires him (although their differences almost break them).

Doleful complications ensue with the Basts in which Leonard (Joseph Quinn, above, 2017) becomes much more than a pet project to Helen Schlegel, alienating Margaret, who seeks to protect Henry from ‘unpleasantness’. For his part, the poor are the way of the world. The guilt-ridden ones, the Schlegels, turn out to lack the material position to help the couple and Henry Wilcox recoils indignantly when he discovers Bast’s wife to have been a youthful indiscretion of his own years ago. Hence the couple suffers, the victims of bourgeois do-gooding gone awry. Actually the story is a gently tragic comedy of errors supplying hypocrisy and denial in large portions. Both film and mini-series offers up a very sharp portrait of class pretension.

As for which of the productions does it better, the Merchant-Ivory film versus the 4-part mini-series, need one choose? The former is too special for words, Emma Thompson winning an Academy Award for her fresh, original Margaret, is truly one of the most engaging heroines in cinema. Helena Bonham Carter is entirely magnetic as Helen— her face all storm-clouds over her impossible brother-in-law Henry (Anthony Hopkins).

Ailing Ruth Wilcox is classic Redgrave — oh how you believe and feel for the grande-dame and wonder that son Charles, the terrific Mr. Wilby (doing a prescient Trump Jr. imitation) and daughter Evie, Jemma Redgrave (niece of Vanessa), have so little of their mother’s generous spirit about them. Although just over two hours, the film packs in Forster’s spritely essence, warm heart, and pointed social satire. (Click here for TrustMovies review of the new boxed set released in 2016 which captures the magic of the Merchant-Ivory.)

But the mini-series is also fine; conversations are deeper, more revealing of E.M. Forster’s social commentary, although the episodes lack the glowy effervescence and pungent satire of the film and sometimes plod. The casting of Alex Lawther [for a look at this young actor's versatility, see him in Goodbye Christopher Robin, Ghost Stories and the ace Netflix series, The End of the F***ing World) as Tibby, the youngest Schlegel and a slightly snobbish Oxford student and droll bookworm, and Tracey Ullman as Aunt Julie are perfect additions to the main cast: Haley Atwell and Matthew Macfayden as Margaret and Henry, (above), Philippa Coulthard, Mr. Quinn, and Julia Ormond. (Lonergan reduced Ormond’s role as Ruth Wilcox so jarringly that the matriarch’s importance to the story is hurt.)

It would seem no one could measure up to a character as unforgettable and charismatic as Bonham-Carter’s Helen, and even though she takes the prize, you will still be charmed and attracted to the winsome Coultard (shown above, with the outcome of the ‘unpleasantness’ she caused Margaret and Henry because of her friendship with Leonard Bast). Also Ms Atwell, whose intelligent, expressive Margaret holds her own against Emma Thompson’s magnificence, still is not Thompson’s Academy Award winner.

On balance the mini-series is lovely if leisurely Edwardian pieces set in a milieu of social change (the pragmatic and imperialist vs the cosmopolitan and intellectual) are your cup of tea and the original if you simply want to know the story of Forster’s beloved work and are up for a completely faithful, joyous, and beautiful film. The Merchant-Ivory is a work of art, but I would not have missed the mini-series (and Tibby and Aunt Julie, below). A Forster fan should know both.

We are left with the question of the effect of Forster’s sexuality on plot and theme. For one, the drama in both film and series is sexless — its romanticism lacking in romance or sexual tension. The tension is class-related. Wendy Moffat’s revelations help here, as well as common sense. Forster did not have his first sexual experience until his late 30’s, years after writing the novel. Underneath his project to demonstrate ‘human connection’ must have lurked his own unrealized desire for the perfection of love-and-sex melded; stories of heterosexual love were incongruous with his own being. But over-analyzing the topic sells short Forster’s profound humanity. There is value in human connection between opposites as among all, sex having nothing to do with it. (During the seasons of this very political era, however, one is predisposed not to seek connections with opposites.)

At any rate, Moffat writes that after Forster became sexually active and had a series of romances, the marriage plot fiction became a masquerade. His growing personal contentment led him to avoid publishing fiction in favor of social and literary criticism. He kept his homosexual-themed writings private. (He is shown below, in later life, with friends).

The above post was written by our

monthly correspondent, Lee Liberman