"My bell rang this morning, I didn’t know which way to go. I had the blues so bad I sat down on my floor. Daddy Daddy Please come home to me. I’m on my way crazy as I can be…."

Or in Prove It on Me Blues:

"Went out last night with a crowd of my friends. They must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men. It’s true I wear a collar and a tie, Makes the wind blow all the while. Don’t you say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me. You sure got to prove it on me."

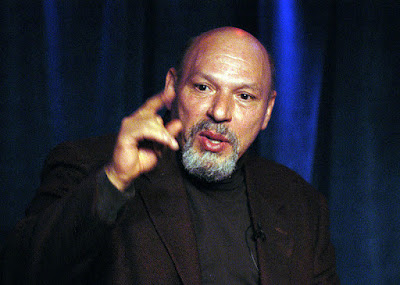

Ma says: “that’s life’s way of talking. You don’t sing to feel better. You sing cause that’s a way of understanding life.” Bawdy, butch, snaggle toothed, Ma Rainey grew her fame as mother of the blues out of the misery of Jim Crow South, says director George C. Wolfe. Blacks told their story through the blues, singing “I will not be passive... I will be defiant in my existence, I will be joyful… and I will dare you to try to stop me in my defiance.” (Below, Wolfe, c, with Viola Davis as Ma, and Chadwick Boseman, as Levee)

The uncertainties of the cotton crop and the brutality of share-cropping led to the great migration north (1915-1970) of six millions, offering wage labor in factories and the deceptive lure of a better life.

Ma Rainey helped herself to a pinch of hope—she grudgingly left her home in Columbus GA at the pinnacle of her career to record her music with her band for Paramount Records in Chicago. Born Gertrude Pridgett, She began performing as a teenager, and traveled with minstrel and vaudeville shows. Later she combined minstrelsy forms of the 1800’s with country blues that she heard on the road (archival photo below).

“Her blues is a blues of defiance, not...of despair”, explains Wolfe. And coming from so adoring a following, Ma brought her own agency with her. Says Coleman Domingo, bandmember Cutler in the film, “she didn’t cop to the social norms of what a woman should be…she was loud...brash. She...wanted her money up front...she demanded respect…'This is my gift. This is my talent. You want me to sing, you honor it'.” Ma knew that to the white recording studio owner, her music rang the studio cash register; he would give her no deference once her songs were recorded — so she extracted what deference she could up front.

Viola Davis quoted in the NYT: “In Ma Rainey, everybody’s fighting for their value and the thing that holds us back is being Black...I wanted that to be a part of Ma Rainey... what lay in the heart of her being. Which is: I know my worth.” Davis captured her rage and entitlement in her affect. (below, she arrives annoying late to the recording session with assorted demands).

A proud bisexual, Ma mentored a young Bessie Smith, who became much better known and easier to represent, more marketable than Ma, herself. Hence it took playright August Wilson (below, 1945-2005) to resurrect Ma Rainey from the 1920’s and give her voice in one of his cycle of plays about everyday lives, winning 3 Tony’s following its original Broadway run.

Ma arrives to even more approving social politics of the Georgia of today — the film is an awards contender for both Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman. Wolfe described Ma’s affect as ‘Black Southern Kabuki...a kind of style and look and glamour’, drawing on the look of Apollo Theater chorus girls who used watered-down shoe polish on their faces — Ma’s cross of minstrelsy and black southern expression.

Wilson chose a Chicago rehearsal and recording session at the peak of Ma’s career to write her into life. While she brought her long history with her, Chadwick Boseman’s character, Levee, the youngest member of the band, represents the agency of youth. Levee has his own arrangement to a Ma song, and he beats it to death to get his way until a confrontation occurs between him and the older band members, then with Ma.

But Levee is thwarted, showing us, as we learn his history and the baggage he carries on his back, that the black experience is rarely not at the wrong end of the stick. Said Viola Davis (NYT, 12/20/20): “There was a transcendence about Chad’s performance, but there needed to be. This is a man who’s raging at God, who’s lost...his faith. So [Boseman has] got to...go to the edge of hope and death and life in order to make that character work. Of course, you look back on it and see that that’s where he was.

And so we arrive from slavery and early Black expression to the present-day of near majority minority population that has led to violent backlash — an openly racist administration (2017-2021) and resistance to the backlash by Black Lives Matter, growing demands for reparations, fixing unequal policing and justice, and presence in our politics of more black and minority leadership. For her part, Ma Rainey helped justify the rewriting of social norms for black and gay artists — I exist, I am who I am.

This is the final tweet from the account of Chadwick Boseman, August 2020. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is dedicated to him; it was his last time on screen.

NBC offered this tribute to his extraordinary life: A Tribute for a King