Meeting Michelangelo Frammartino proves one of the singular treats of TrustMovies' cinematic life, not only because of the richness and beauty of Le Quattro Volte, and now this new "cinematic installation," Alberi, but because the man himself seems as beautiful inside and out as are his films. So fully alive and filled with wonder and pleasure does he sound and appear that he is at once propulsive and contagious -- in the best of ways -- as he speaks about his latest work.

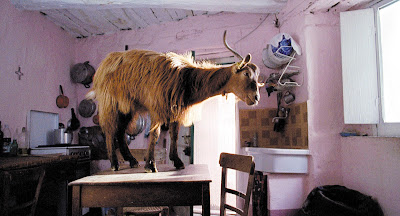

The first thing Frammartino does as he sees me coming toward him (thanks to my rather large height) is to tell me that I should have played one of his man/tree characters (above, center) in Alberi, which translates into English as "trees." Frammartino himself is on the small side, but so full of energy is he that he seems about twice my size. Alberi is his 28-minute ode to nature, ceremony and tradition, in which his camera (and we) wake to a morning in the midst of a forest in the hills of Southern Italy (locations were Armento, Potenza and Basilicata), then slowly come to life, moving around, over and into a mountain village not unlike the one used for Le Quattro Volte, which was filmed in Calabria. (The village used here seems larger, or maybe more compact, than that in LQV.)

The wind blows, bells toll, and a group of men leave for that nearby forest, carrying with them some small hand tools. Once in the forest, they begin stripping trees of their ivy growth and small branches, and before we know it, suddenly -- well, this is for you to see and gasp at. The film ends with a kind of traditional ceremony that eventually brings us back to that initial image -- but now in a very different manner.

There is no dialog in the film, just image and sound. And beauty. That's more than enough. While some of the images may put you in mind of the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul or The Wicker Man, this is uniquely Frammartino. Oh, yes -- one more thing: These films are not documentaries, they are narratives, although they use the documentary style and are based very closely on real life, tradition and ceremony, as they are found in these villages. But the artist has tweaked them all to serve his goal. Alberi plays now through April 27, via the Tribeca Film Festival and MoMA's PS1.

While his work may keep the fellow youthful, it does take a good deal of time to produce. Frammartino spent five years making the 88-minute Le Quattro Volte and a full year making this new (and not even a half-hour-long) film. "I don't work so quickly, it is true." By comparing the country of Italy to a shoe and then using his own foot as an example, the artist points out the areas of Italy, both of which lie in the south, where his films were shot.

Still, there is something primal, maybe pantheistic, in the work of this man, and in his personality, too. You cannot watch his films or spend even a little time with him without being, in a sense, conver-ted. But Frammartino is not proselytizing; he's just being himself.